09 Mar FEMINIST ARTICULATION: THE KEY TO DEFENDING LABOR RIGHTS

FEMINIST ARTICULATION: THE KEY TO DEFENDING LABOR RIGHTS

In March, 2020, I had just recently started working as ProDESC’s Deputy Director of Operations. During the previous eleven years, my professional life had been marked by working in an international feminist organization and in environments exclusively of, for and with women and women human rights defenders. Joining another feminist organization working for the defense of land and territory and human labor rights with mixed collectives in a country like Mexico provides the possibility of stepping into this environment and contributing my international experience to continue strengthening and constructing ProDESC’s transnational work.

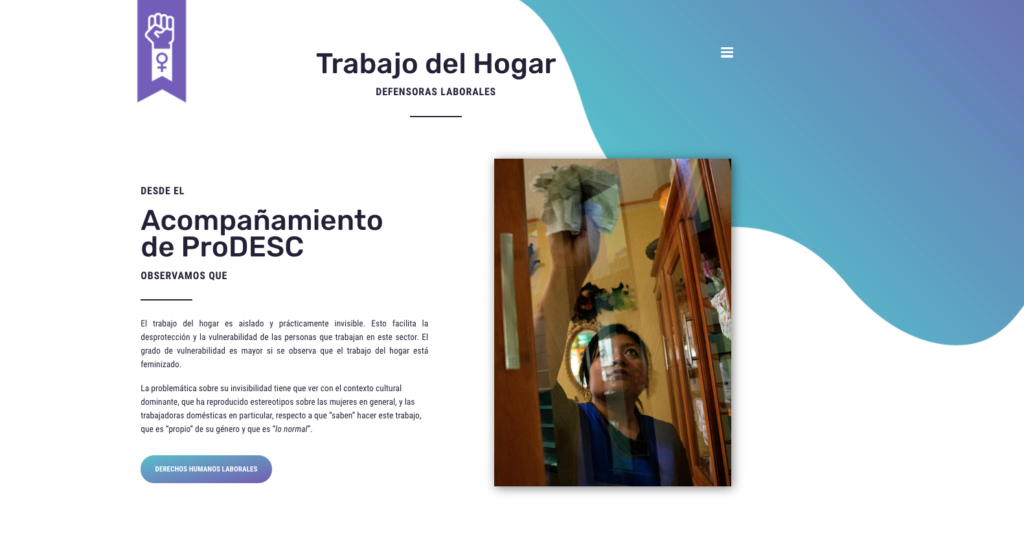

ProDESC accompanies and forms part of the National Coordination of Women and Men Human Labor Rights Defenders (CNDDHL), part of the work that I am in charge of coordinating. As I delved more deeply into the work, that had been carried out since 2013, I learned about the achievements of 2019 to make the work visible through presenting its Political Agenda. The need and importance of continuing to reinforce this space became clear.

With great enthusiasm and only a couple of weeks away from meeting the colleagues who form part of the Coordination, COVID-19 took us by surprise. We were no longer able to meet in person and, like many others, were forced to resort to virtual technologies in order to be able to proceed with the meetings and plans that we had already scheduled for the year. We had thought that in 2020 we would be traveling the country to continue presenting our Political Agenda and use strategy and vision to outline our advocacy roadmap. We foresaw that this would enable us to advance toward fully ensuring women’s labor rights in Mexico, along with other women’s organizations.

The context of the pandemic shifted our focus to discuss the emergency and the immediate impact it was having on women’s work:

- Layoffs with no labor guarantees for domestic workers;

- Impossibility of traveling or traveling under risk for women seasonal migrant workers;

- Health risks for women agricultural workers;

- Maquila close downs with no guarantee that the workers would be rehired or continuing to work without the appropriate protection to preserve health.

In addition, there was a crisis in child care and elderly care, which mostly befall women, as well as our own challenges as women defenders having to combine working from home with seeking ways of collectively constructing our movements in a scenario that hinders the possibility of meeting face to face.

WOMEN

To see this situation from the perspective of data regarding the pandemic’s impact on women’s employment, ILO states that more than 24 million jobs are at risk of being highly affected, representing 44 percent of the working population. In addition, more than 50 percent of women’s employment is at risk. ILO also points to an aspect that we feminists have always made visible: that women suffer preexisting negative conditions in the labor market. It is likely that the crisis will worsen these fragile conditions.

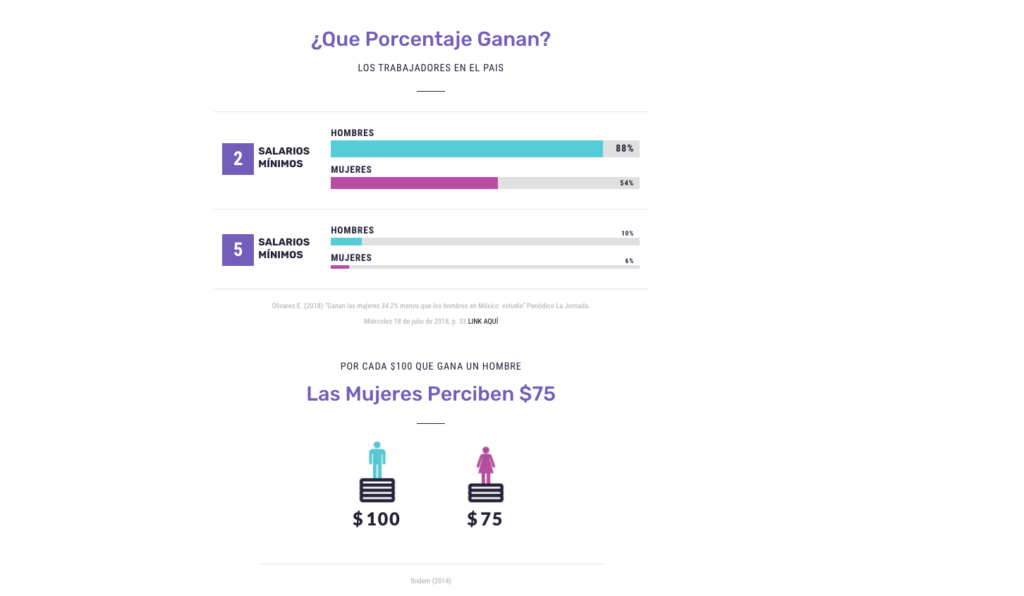

ILO observes that women have greater labor participation in low-risk sectors (as defined by ILO), such as education and health. However, upon analyzing women’s total participation per activity sector, more than 11 million women workers are employed in sectors with a very high risk of contagion, representing 53 percent of the women workforce in Mexico. The data reveal a complex panorama which in terms of women’s day-to-day life in Mexico translates into an increasing inability to sustain our life and that of our families. It is worth recalling that the Mexican government recognizes that one of the greatest transformations in Mexican households in recent years has been an increase in women’s responsibility to sustain the household. According to data from the National Household Income and Expenditure Survey (ENIGH), in 2008, 24.7 percent of all households were sustained by women, reaching 28.5 percent in 2018, representing a 12 percent growth rate. In the same period, the households in which men were the breadwinners only grew at a 4.4 percent rate. In concrete terms, this means that women have been and will be the population group more deeply affected by the aggravation of the structural inequalities existing before the pandemic. These inequalities are bound to increase due to both the pandemic and the economic crisis it has triggered. Considering that women were already at a disadvantage in the labor world, the effects of the pandemic are likely to lead to greater disadvantage in aspects that ILO has identified, such as:

1) the number of jobs (in terms of employment, unemployment, and underemployment); 2) the quality of work (regarding wages and access to social protection); and 3) the effects on specific more vulnerable groups facing adverse consequences in the labor market.

With this scenario in mind, ProDESC set forth that it was of crucial importance to continue moving forward in the construction of new and better collective articulations with women colleagues who have chosen to continue thinking creatively about positioning a feminist labor agenda by and for women, and turning this pandemic into a strategic opportunity. We have witnessed the imminent economic crisis that has started since the lockdown began, as well as the vulnerability existing in our work, which became aggravated in recent months with the threat of a possible worldwide recession. In the face of this panorama, as organizations, both CNDDHL and ProDESC have decided we cannot remain idle.

ACTIONS

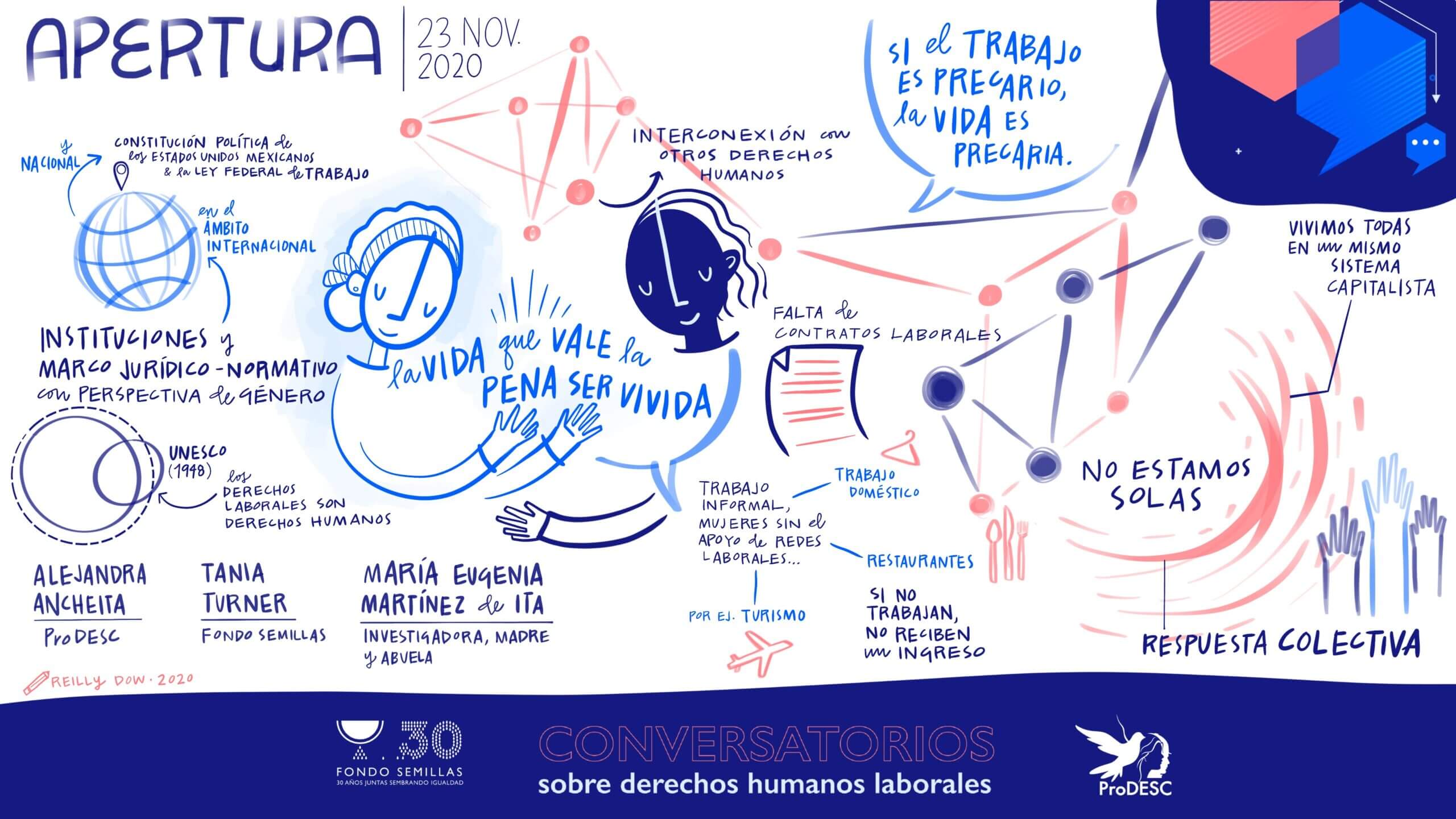

One of these collective articulations was conceived and consolidated with our allies and friends from the Semillas Fund . through the Intergenerational Conversations with Women Human Labor Rights Defenders held from November 23 to 27, 2020. During that week, hundreds of women defenders and organizations from Mexico and Latin America dialogued, exchanged information, and reflected upon themes of relevance for labor rights to be vindicated and move forward, imagining and sharing strategies within the context of a global pandemic the effects of which will be felt in our lives for years to come.

The day conclusions were presented, we were privileged to hear Susana Plascencia’s marvelous synthesis of the week’s analysis, debate, and reflections. I would like to share some glimpses of this process so that we can continue reflecting together. The introductory session opening the dialogue clearly confirmed that:

- As women, we work more than men and the pandemic has tripled women’s work (in domestic spaces).

- We are confronted by extreme economic informality, low income levels, severely unfavorable working conditions, labor precariousness, and high unemployment levels.

These issues have led us to resort to feminist economics as a benchmark to rethink the relationship between society and the market and that this relationship occurs within what María Eugenia Martínez has called “a life worth living.”

DIALOGUE BETWEEN ALL OF US FOR ALL OF US AS WOMEN

Panel 1 on Feminist Economics delved deeply into understanding the analytic framework and actions of Feminist Economics, which allows us to:

- Make visible dimensions hidden by conventional economics (caring work, the gender dimensions of the global chain of value, and life sustainability).

- Have more transformational tools.

- Construct an economy that serves people rather than the interest of large-scale corporations prevailing over human life, as currently occurs.

Panel 2 addressed the importance of getting to known the content of trade agreements States sign. It was of key importance to understand the implications of the USMCA vis-à-vis women workers’ reality and the provisions it includes, which are still seen as promissory obligation faced by the State in order to comply with labor rights. We reflected upon how institutionality does not ensure access to rights, which is why it is so important that we organize in order to exercise influence. Lastly, we agreed on the need to learn and document the content of trade agreements that impact our lives with the understanding that “an unknown right cannot be defended”.

Panel 3 on Labor Violence helped us see this theme from a comprehensive and gender perspective, acknowledging the multiple dimensions affecting our lives as women when we face this form of violence in the workplace. We observed that from a social perspective, it is an issue that has not been made visible, forcefully restricted to the worker’s private sphere and hardly vindicated by labor unions. Another of the challenges we face as a movement is carrying out advocacy work in favor of ratifying ILO Convention 190. Panel 4 on Informal Work dismantled the myth that informal work does not contribute to the economy. Using data that refutes this myth, we were able to confirm that in 2018, the informal economy represented 22 percent of the Mexican GDP. Worker surveys conducted during the pandemic also evidenced labor precariousness and a lack of access to rights, as well as the limited scope of aid programs in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. Our last but not least important discussion took place in Panel 5 on Labor Rights and Migration. This panel evidenced the greater vulnerability women and migrants face vis-à-vis their labor rights being breached or simply not being unable to exercise them, in addition to aggravating factors of the pandemic. Some of the situations faced by migrants are: the difficulty of accessing benefits and State protection programs, deportations, complex regularization processes, and discrimination. One of our colleagues made an extremely important reflection: “We have to start realizing that migration is a social movement for life.”

On our Conversation website you can access the recording of the sessions and materials shared by the facilitators, as well as the reflections and in-depth conclusions coming from each panel.

This week of meetings confirmed that women workers’ human rights violation, as well as the lack of guarantees to safeguard women’s livelihoods and health are not new, leaving even more evidence of the preexisting gender gap women face upon attempting to access employment under the same conditions as men, as well as the crisis in the caretaking system. As feminists, once more, as an item on our agenda, we included the refusal that our lives and jobs be sacrificed in order to rescue the current economic crisis. I firmly believe that it is imperative to have a feminist perspective and feminist proposals if we are to salvage this crisis in a way that is different from other attempts. These are indispensable for a serious reflection about reorganizing life within this new context. As Aleida Hernández Cervantes states, we must move towards a “new social order that we could call a Feminist Social Pact” which will enable us to “transit towards regulating in order to benefit life rather than things.”

1)Articulación feminista: clave en la defensa de derechos laborales

2)Articulación feminista: clave en la defensa de derechos laborales

3)Articulación feminista: clave en la defensa de derechos laborales

4)Articulación feminista: clave en la defensa de derechos laborales